Failure to Function: Ornamental Refusals

Jeffrey Turben | May 26, 2021

Introduction

Ornamental refusals are on the rise—with the USPTO issuing upwards of 50 ornamental refusals on a single day. The refusal stems from the inherent nature of the mark itself as well as improper display of the mark on specimens, but with the right arguments, a merely ornamental office action can be overcome.

When an applied-for mark is found to be merely ornamental—that is, just a decorative feature—it will be refused based on its failure to function as a trademark. A decorative feature may include, but is not limited to, words, designs, slogans, or trade dress. Ornamentality lies on a spectrum and certain incidentally ornamental features may be accepted for registration, whereas purely ornamental features will not be accepted for registration. To decide where to plot the applied-for mark on the ornamentality spectrum, trademark examiners look at the following factors:

(1) The commercial impression of the applied-for mark

(2) The relevant practices of the trade

(3) Secondary source, if applicable, and

(4) Evidence of distinctiveness

This article will provide an in-depth discussion of each of the factors contributing to ornamentality and will suggest strategies for overcoming these factors.

Commercial Impression

When evaluating the commercial impression of the mark, the examiner will ask whether the applied-for mark is used or otherwise positioned in a way as to actually be perceived as a trademark in the mind of a reasonable consumer. U.S.P.T.O., Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure § 1202.03(a) (Oct. 2018). Specifically, the examiner considers whether the applied-for mark principally serves as a means by which consumers may differentiate applicant’s products. See In re Lululemon Athletica Canada, Inc., 105 U.S.P.Q.2D 1684, 1686 (T.T.A.B. 2013) (“[A] design which is a mere refinement of a commonly-adopted and well-known form of ornamentation for a class of goods would presumably be viewed by the public as a dress or ornamentation for the goods,” rather than an indicator of origin.)

In making a determination whether the applied-for mark is perceived as a trademark, the examiner will consider the size, position, and prominence of the applied-for mark as depicted on the specimen of record. U.S.P.T.O., Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure § 1202.03(a) (Oct. 2018). The smaller, neater, and more uniform the applied-for mark appears on the specimen, the more likely it is to be held to function as a trademark. Id. Conversely, the larger, more prominent, and louder the applied-for mark appears on the specimen, the more likely it is to be held to not function as a trademark, but rather serve as a mere decoration or ornamentation. Id.

Additionally, the examiner will consider the design elements or style of the applied-for mark in the context of the specimen. See In re Lululemon Athletica Canada, Inc., 105 U.S.P.Q.2D at 1689 (rejecting a per se rule that the size of the applied-for mark is the only factor to consider in a commercial impression analysis, the TTAB held that other factors should be considered, including the style and design elements of an applied-for mark in the context of the specimen of record).

Practical Application:

TTAB finds commercial impression of applied-for mark is merely ornamental due to large size and simplicity of mark.

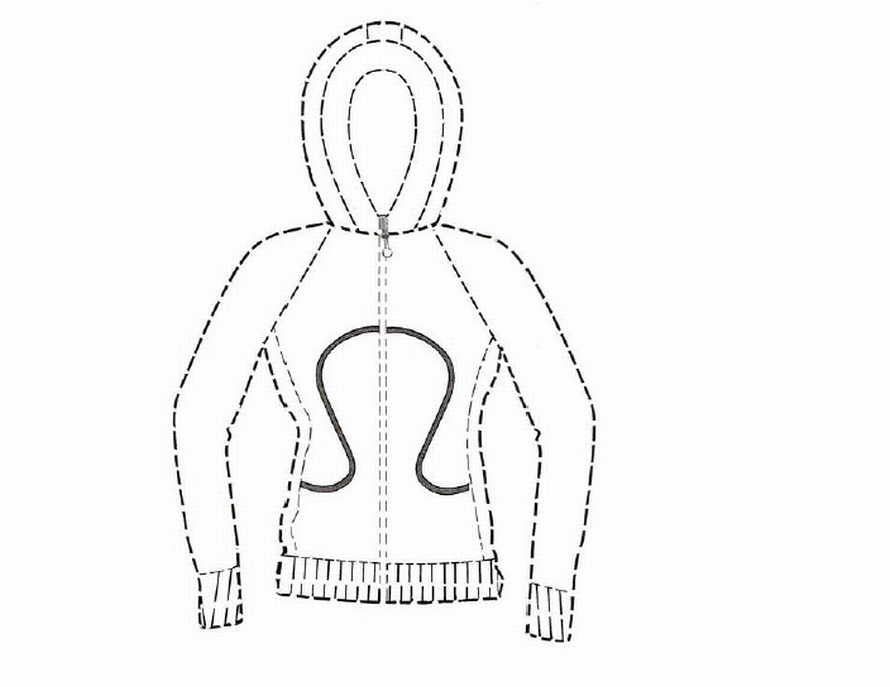

In In re Lululemon Athletica Canada, Inc., Lululemon sought to register its Omega-esque logo on the front of a hoodie. The examiner initially refused registration because the mark was found to be merely ornamental.

On appeal, the TTAB affirmed the examiner’s contention that the mark was ornamental. Key to the TTAB’s finding was a lack of evidence suggesting that consumers would perceive the applied-for mark as anything more or other than mere ornamentation, suggesting that consumer surveys, etc. could be helpful in overcoming this hurdle. In re Lululemon Athletica Canada, Inc., 105 U.S.P.Q.2D at 1686-90. The Board noted industry practices and highlighted examples of large and prominent marks not functioning as trademarks, and other examples in which similar marks did function as trademarks. Id. The Board found that the Lululemon mark was too simple, in contrast with the highly-stylized marks that were granted registration despite large and prominent location on those marks’ specimens of record. Id.

Overcoming a Refusal:

How to demonstrate that the applied-for mark gives the commercial impression of a trademark and is not purely ornamental.

To successfully demonstrate that an applied-for mark gives the commercial impression of a source indicator, the applicant should introduce evidence showing that the applied-for mark is seen as only incidentally ornamental. Accordingly, the applicant should address the examiner’s reasons for refusal and introduce the following types of evidence:

(1) Advertising and marketing information,

(2) Consumer behavior information,

(3) Search-Engine-Optimization Data, and/or

(4) Marketing campaign and sales information.

The Relevant Practices of the Trade

When conducting an ornamentation analysis, trademark examiners will also try to place an applied-for mark’s use in the context of the industry in which the applicant operates. U.S.P.T.O., Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure § 1202.03(b) (Oct. 2018). The examiner will consider whether the design elements and configuration of the mark are arbitrary or unique in relation to established industry practices. Id. The examiner will determine whether the mark’s design elements or configuration are a mere refinement of industry practices and whether consumers understand these practices as creating mere decoration or ornamentation. Id.

Additionally, if an established industry practice suggests that the mark is ornamental subject matter that consumers would not likely perceive as being able to function as a trademark, the applicant may have a higher burden to produce evidence to demonstrate distinctiveness and use. Anchor Hocking Glass Corp. v. Corning Glass Works, 162 USPQ 288, 292-99 (TTAB 1969).

Practical Application:

TTAB finds that applied-for mark is merely ornamental because it is common industry practice to spell words/phrases with letter-shaped jewelry links

In In re Peace Love World Live LLC, the applicant’s mark “I LOVE YOU,” shown as stylized letters linking to form a bracelet, was refused as merely ornamental.

The TTAB reasoned that because it was common industry practice to manufacture bracelets with letter-shaped links forming slogans or phrases (including “I LOVE YOU”), the mark would be perceived by consumers as mere ornamentation and, thus, failed to function as a trademark. In arriving at such a finding, the TTAB noted information submitted by the examiner, including examples of industry practices.

Because the applicant failed to produce evidence suggesting that the mark functioned as anything more than ornamentation and because it is common industry practice to form bracelets out of links consisting of letters as a part of a phrase or slogan, the applied-for mark was nothing more than a mere refinement of a common and well-known form of ornamentation, which is not registrable subject matter.

Overcoming a Refusal:

How to demonstrate that the applied-for mark is not purely ornamental because it is unique with respect to industry practice.

If an applied-for mark is refused as being merely ornamental because relevant industry practices suggest that the applied-for mark does not differentiate the applicant’s products or services, the applicant can overcome the refusal by producing evidence showing uniqueness, arbitrariness, or fancifulness with respect to the industry practice. For example, if it is a common industry practice to sell button-down shirts with collars, and an applicant attempts to register a certain form of collar, an applicant might be able to overcome a potential refusal by demonstrating both that the collar is unique, fanciful, and arbitrary compared to industry practices, and showing that consumers recognize the differences between the applied-for mark-collar and other collars.

Secondary Source

If an applied-for mark is being used in an ornamental or decorative manner, it may still register if the applicant is able to show that it would be recognized as a mark through its use with goods or services other than those being refused as ornamental. In this situation, the applicant must point to a secondary source including:

(1) Ownership of a U.S. registration of the same mark for other goods or services that’s both 1. on the Principal Register, and 2. based on use in commerce under §1 of the Trademark Act;

(2) Ownership of a U.S. registration that meets the following criteria: 1. It is listed on the Principal Register of the same mark for other goods or services, 2. The application is based on a foreign registration under §44(e) or §66(a) of the Trademark Act, and 3. The mark’s affidavit or declaration of use in commerce under §8 or §71 has been accepted;

(3) Non-ornamental use of the mark in commerce on other goods or services; or

(4) Ownership of a pending use-based application for the same mark, used in a non-ornamental manner, for other goods or services.

U.S.P.T.O., Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure § 1202.03(c) (Oct. 2018).

Practical Application:

TTAB finds that an applied-for mark conveys secondary source and is incidentally ornamental.

In Disorderly Kids LLC v. Atwood, the petitioner sought to cancel the registered mark SMILE MORE, alleging failure to function due to the mark being purely ornamental. The SMILE MORE mark was registered by Roman Atwood, a prominent YouTube personality with over 9 million subscribers. The mark was promoted throughout his video content on a daily basis for a number of years and appeared on merchandise listed on Atwood’s website, The Official Smile More Store.

The TTAB found that the mark was able to convey a secondary source and was therefore incidentally ornamental. In making this determination, the TTAB indicated that the submitted specimens showed the mark SMILE MORE in a non-ornamental way, clearly associated with the mark owner and his YouTube channel. Additionally, the TTAB considered it significant that the respondent enforced its rights to the mark. When third parties attempted to sell merchandise featuring the mark SMILE MORE, the respondent took action. In particular, the respondent sent cease and desist letters and obtained agreements to stop selling infringing products when third parties used the mark SMILE MORE in attempt to associate themselves with respondent and his YouTube channel.

The TTAB decision provides an example of a mark that conveys a secondary source as a result of effective marketing and product positioning. In this scenario, the mark is considered to be incidentally ornamental and functions as a trademark.

Evidence of Distinctiveness

Ornamentality is not an absolute bar to registration. An incidentally ornamental mark may still register if the mark owner has demonstrated acquired distinctiveness pursuant to 15 U.S.C. § 1052(f) (§2(f)). A mark has acquired distinctiveness if the owner is able to show that the mark serves a means by which consumers can differentiate applicant’s products. Read more about demonstrating acquired distinctiveness here.

Putting It All Together:

Demonstrating multiple factors to overcome a merely ornamental refusal

Anheuser-Busch applied for the mark THE CLUMSY SWORD, but it was initially refused as failing to function and being merely ornamental.

Applying Lululemon, as well as Peace Love World Live, the examiner found that the applied-for mark was large, prominently displayed and positioned in such a way that consumers would not perceive the mark as a source-identifier. Office Action Regarding U.S. Trademark Application Serial Number 87724349.

In response, Anheuser-Busch argued that (1) the applied-for mark was inherently distinctive and only incidentally ornamental, and that (2) the applied-for mark is an indicator of secondary source, and, therefore, consists of registrable subject matter. Response to Office Action Regarding U.S. Trademark Application Serial Number 87724349. The attorney used the following argument:

Commercial Impression

Anheuser-Busch argued that the examiner placed too much weight on the positioning and size of the mark.

The Relevant Practices of the Trade

Anheuser-Busch set forth evidence showing that consumers would recognize the applied-for mark as a source indicator. They produced examples of similar clothing items that featured a large and prominent display of a registered mark, including items by Adidas, Hollister, Under Armour and Fubu—that demonstrated that it is a common practice to conspicuously display a logo or trademark in the manner of the specimen-of-use. Anheuser-Busch concluded that the applied-for mark is incidentally ornamental because the examiner seemingly applied a per se rule regarding the size and prominence of the mark, which was rejected in Lululemon, and failed to analyze the actual trade practices in the relevant industry.

Secondary Source

Anheuser-Busch argued that the applied-for mark served as a secondary source, explaining that “THE CLUMSY SWORD” is the name of a fictional pub, developed as part of the extremely successful viral Bud Light Kingdom advertising campaign. At the time of the proceeding, the applied-for mark had been featured in advertising and marketing content that generated more than 750k impressions across YouTube and television advertising. Citing In re Carlson Dolls Co., where the Board held that consumers have a reasonable expectation that goods bearing the mark of a fictional character emanate from or are, at the very least, marketed or produced under license from the entity which created the character, Anheuser-Busch further argued that its customers have a reasonable expectation that goods bearing the applied-for mark originate from Anheuser-Busch and not some other producer. Finally, Anheuser-Busch argued that because of the promotional nature of the shirts, consumers would view Anheuser-Busch as the origin of the goods. Anheuser-Busch produced evidence suggesting that consumers are accustomed to promotional merchandise bearing a trademark in the manner of the specimen-of-use and that the mark would convey a source.

Evidence of Distinctiveness

In this case, Anheuser-Busch argued that the mark was inherently distinctive, thus there was no need to set forth evidence of acquired distinctiveness.

As a result of persuasive arguments and evidence showing that the mark was not merely ornamental, Anheuser-Busch was able to successfully overcome the initial refusal and register THE CLUMSY SWORD.

Ornamental Refusals and Service Marks

While service marks will not be refused as being ornamental, they are subjected to similar scrutiny.

“[I]n determining whether the public would perceive the proposed mark as a service mark, i.e., an indicator of the source of the services, or merely as a decorative or ornamental feature, factors considered by the examining attorney include the commercial impression created by the display of the subject matter on the specimen, any prior registrations of the same or similar matter for similar goods, promotion of the subject matter as a service mark, and the practice of the relevant trade.” In Re Ingram Micro Inc., No. 78321253, 2011 WL 6012207, at *2 (Nov. 15, 2011).

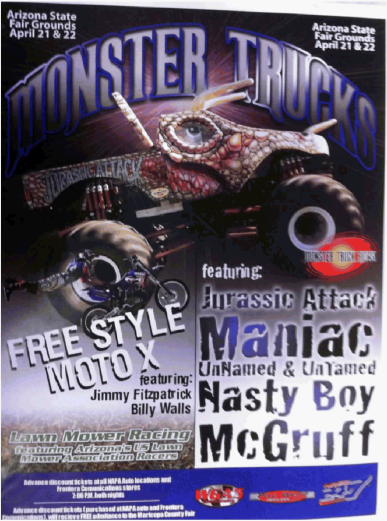

In In re Frankish Enterprises Ltd., the TTAB reversed the examiner’s refusal of a service mark that consisted of a body design for a monster truck, stylized as a fanciful, prehistoric creature, used in connection with the applicant’s services, monster truck exhibitions.

In the Final Office Action, the examiner found that the applied-for mark failed to function as a trademark because the evidentiary record did not support a finding that consumers would, given the relevant trade-practices, perceive the design as an indicator of source. The examiner argued that it is common practice for monster trucks to appear in a wide variety of designs for entertainment purposes.

The TTAB reversed the examiner’s findings, instead determining that:

-

Applicant’s mark was inherently distinctive,

-

Given the arbitrary and fanciful nature of the design, the mark was more than a mere refinement of a common industry practice, and

-

The evidence clearly established a link between the mark and the services with which it was being used.

The TTAB found it significant that the applicant submitted specimens showing the mark used in connection with its services, namely “jumping over and crushing smaller vehicles and otherwise entertaining fans with the truck’s size, power and sheer awesomeness.” The Board further noted that the design of the truck was distinct with respect to a search of over 100 other monster truck designs.

The Board also emphasized that consumers would specifically associate the design with the applicant’s monster truck services. The Board made this determination upon reviewing a specimen containing an advertisement depicting multiple monster truck drivers.

Because the applicant’s mark was prominently displayed and used in connection with monster truck exhibition services, it was held that the mark was registrable.

Conclusion

Overcoming an ornamental refusal can be a challenge. However, by setting forth the proper evidence, applicants can successfully argue that the mark is a source indicator and not merely a decorative feature. Each of the factors—commercial impression, relevant practices of the trade, secondary source, and evidence of distinctiveness—are important considerations. The more evidence you are able to demonstrate for each factor, the stronger your argument will be that the mark at issue is not ornamental and rather, a source indicator.