Alt Legal Connect Session Summary: IP Matters: Practical ways that IP lawyers can advance social justice

Alt Legal Team | September 14, 2021

On Tuesday, September 14, Christian Williams, Founder of Bevel Law, Tyra Hughley Smith, Founder of Hughley Smith Law, and Kimra Major-Morris, Founder of Major-Morris Law presented the session, “IP Matters: Practical ways that IP lawyers can advance social justice.” The presenters provided a practical perspective on how IP lawyers can contribute to social justice in their everyday lives.

Presentation Materials: Click here

View Recording (free): Click here.

Introduction

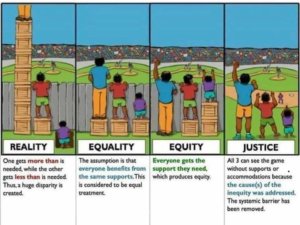

Christian began by providing definitions of some important terms that are part of this conversation:

- Social Justice: The idea that all people should have equal access to wealth, health, well-being, justice, privileges and opportunities regardless of their legal, political, economic, or other circumstances.

- Equality: Each individual or group of peoples is given the same resources or opportunities.

- Equity: Recognizes that each individual or group of people has different circumstances and allocates resources and opportunities needed to reach an equal outcome.

- Racial Justice: The systemic fair treatment of people of all races, resulting in equitable opportunities and outcomes. Not merely the absence of discrimination and inequities, but a specifically proactive and even preventative approach.

- Race: The idea that people can be divided into different groups based on physical characteristics that they are perceived to share such as skin color, eye shape, etc., or the dividing of people in this way.

Christian noted that we talk about racial justice because social constructs like race have societal repercussions in everyday society.

Historical Context of Race and IP

Christian moved on to discuss the historical context of race and IP. Art 1 Sec 8 of US Constitution, which is the basis of patent and copyright law in the US, provides a benefit to an author and inventor. Who qualifies? Pre-Civil War, enslaved Africans were not considered authors or inventors because they were not US citizens. But this was a problem for slave owners because enslaved Africans were working in the agricultural industry and coming up with inventions that slave owners wanted to patent and take credit for them. In 1858 this issue came to a head when the US Attorney General decided that slave owners could not patent the inventions of slaves. This was not the US Attorney General was an early proponent of racial justice, rather, it was because he determined that enslaved Africans were not citizens who cannot take the patent oath, and slave owners could not honestly take credit for the inventions. Therefore, the inventions of enslaved Africans were simply un-patentable.

When the Confederacy was formed, a law was passed to deal with this issue: the Patent Act of Confederacy. It allowed slave owners to patent the inventions of their slaves. We don’t have a full view of the scope of Black invention in this time, but there was sufficient activity that slave owners felt the need to pass a law to take credit for the inventions of their slaves.

While enslaved Black inventors could not prevent slave owners from patenting their inventions, free Blacks were discriminated against when trying to secure rights. One applicant had the word “colored” added to his patent application by the Patent Office which was not standard practice. Many early Black-owned patents were lost in a Patent Office fire in 1836.

Historical Context of Race and Copyright – Music

Christian noted that African Americans pioneered several major genres of American music, but many artists died divested of copyrights and penniless. The stories she shared showed how Black artists were systemically denied the benefits of copyright and rights to royalties. She noted such distinguished artists as Scott Joplin, the King of Ragtime, who sold half a million copies of sheet music to “Maple Leaf Rag” who died penniless and was buried in an unmarked grave. Similarly, Bessie Smith, the Empress of Blues, was illiterate and relied on someone at her record company, Columbia Records, to manage her career and sign agreements on her behalf – this unfortunately ended with her signing away royalty rights. Billie Holiday sadly died without a will and her estranged and abusive husband got rights to her royalties and her name, likeness, and image. Also notable, Little Richard sold his song “Tutti Frutti” for $50 and at a time where white artists got royalties between 2-3%, Little Richard received no royalties. This was a common practice at the time for Black artists not to receive royalties. In the 1980’s, however, he was able to sue his record label to get some measure of justice

Historical Context of Race and Copyright – Trademarks

Christian explained that in terms of trademarks, the concern is less about stealing of ideas, but we see the way trademarks entrenched racial stereotypes and how under trademark law, racist imagery was protected as valuable company IP. Christian noted that Blacks, as well as other communities have been subject to racial discrimination through trademarks including American Indians, Asian Americans, and Latinx. Christian pointed out several brands that have perpetuated and entrenched racial stereotypes including Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben, and Cream of Wheat.

Current State of Affairs

Tyra provided some statistics showing that law is the least diverse profession in America. The ABA found that only 5% of attorneys are Black, 5% are Latinx, 2% are Asian. The numbers have unfortunately remained consistent even though there have been many efforts at improving diversity, equity, and inclusion in law. Tyra noted that the US population is 13.4% Black, so there is definite disparity in population and representation in the attorney field.

In IP, representation of Blacks is still very low. Most IP representation is primarily by White males. AIPLA estimates less than 2% IP attorneys are African American, 2.5% Latinx, and .5% Native American and that 70% of IP lawyers are male.

Tyra noted that it’s particularly difficult to ascertain the number of Black women in IP. Because of societal constructions, minorities are a monolithic group including men and women, or statistics are simply looking at women and not considering their races. Tyra surmised that if 1.8% of IP attorneys are Black, then a smaller percentage must be Black women.

Tyra then went on to explain why there are so few Black IP attorneys, and particularly Black women IP attorneys. She explained that there are systematic issues of course, but also a lack of STEM training, enabling Blacks to become patent attorneys or enter highly technical fields. Additionally, there is a lack of mentorship. Tyra noted that it can be difficult for minority attorneys to find mentors at the level they want. Tyra impressed the importance of people outside of those communities taking on mentees who don’t look like them. Finally, Tyra indicated that hostile work environments and lack of support particularly affects minorities and women particularly. When women/minorities are not receiving the support they need in Biglaw, they open up their own shops.

Despite the low numbers of Blacks in law and IP, Trya explained that Black entrepreneurship is growing, particularly among Black women. According to the Harvard Business Review, 17% of Black women are in the process of starting or running a new business, which demonstrates higher and faster growth than any other subset. However, Tyra explained that these Black women are lacking resources – their businesses are considered less mature and are lacking funding. While Black women are fastest growing subset of new business owners, they are often facing obstacles that other entrepreneurs don’t face. Tyra explained that this is important because we know representation matters – people often feel more comfortable working with someone who looks like them.

Cultural Appropriation – J’OUVERT, TikTok, BLM, and Catalog Sales

Next, Kimra introduced a discussion on cultural appropriation – the adoption of expression, traditions, artifacts of a certain group without their consent, compensation, without giving credit, and without giving input. Kimra explained that as IP practitioners we are dealing with brand owners and we need to ensure that the proper group gets compensated, we need to ensure input and collaborations, and we need to make socially responsible recommendations.

Kimra provided an example of a recent mishap involving cultural appropriation when actor Michael B. Jordan filed a trademark application for J’OUVERT for alcoholic beverages, specifically noting that the mark had no meaning in a foreign language. However, this was completely untrue. There is a rich cultural meaning around the word J’OUVERT meaning “day break” and signaling the start of Carnival in Caribbean cultures. While Jordan announced that he would rebrand, it is important as IP attorneys to dig deeper and understand the meaning of the word. In this case, there were four other marks on the trademark registry with the word J’OUVERT identifying the foreign meaning of the word – so Jordan’s attorneys didn’t have very much research to do.

Next, Kimra turned to TikTok where Black creators have been upset because they were creating dances and other dancers, not of color, who were copying their moves, were getting more traffic. In cases where a practitioner represents a person who is not of color, the attorney should have discussions with the client if they see that the client is taking off for something creative. Have an honest conversation and find out where it originated. If you discover that the client didn’t create the dance, recommend a collaboration with the originator. It’s a better look for your client, but also you as a lawyer since it is such a sensitive matter given the historical context of not giving people of color credit for their creations.

Kimra then turned the discussion towards Black Lives Matter. She noted that of the 88 BLM applications on the trademark register, none have proceeded to registration, as the USPTO has considered the mark political, but curiously, other marks like CHRISTIAN LIVES MATTER have gone on to register. Kimra cautioned that when things are trending in the news, people race to file related marks. She advised that as practitioners, it’s helpful if we discourage people from trying to file these marks since we can’t protect political speech. She proposed that collaborations are especially helpful in this situation. Kimra cited her experience in representing the family of Trayvon Martin and noted that sending C&D’s was not the most strategic way to handle it and it was better to try to collaborate, because these people using terms related to Trayvon were supporters. Kimra identified another challenge: publicity rights statues which don’t exist in every state. If you live in a state with no publicity rights statute while alive or post mortem, this is challenging. You could consider copyright registrations of family photos if your state has no publicity rights so that you can prevent others from using photos for publicity. You can also incorporate name/image/likeness in the design mark if there’s no right of publicity statute.

Kimra concluded her discussion noting that because of COVID, artists haven’t been able to tour and may artists have turned to selling their music catalogs. Kimra warned: as practitioners, you need consider how many decades people of color were robbed of their IP rights. Instead, encourage your client to engage in license agreements for songs instead of permanently losing the income.

What Can IP Lawyers Do to Promote Social Justice

Kimra – I’ve noticed many brand owners and creative clients are financially challenged and legal fees are out of range for them. What I’ve done is offer payment plans with no penalties. I also do free 15-minute consultations because there is an educational deficit and we can talk about whether you need a trademark or copyright.

Tyra – Education is very important and I focus on the information gap. I have a free Facebook group where I give out free education. I also do pro bono and low bono. I also make it a point to mentor newer attorneys and people moving into the practice area. Also, a lot of practitioners have seen uptick in less-founded Office Actions. I mentioned to the USPTO Director that substantive Office Actions really hurt minority and small business owners and the financial burden creates a gap with Black owned businesses being less mature.

Kimra – It can help to have a team of publicists or PR people and help with messaging.

Tyra – Have diverse, real voices around you all the time in the development phase. Not just a figure head so you can say you’re diverse. Have real people who can provide criticisms without getting backlash. Also, reach out with questions to Black and minority attorneys or HBCUs, and network with minority attorneys. Understand that disenfranchisement has happened, you can do your best to prevent that from happening any further.

Kimra – Rhianna and Fenty – she made a line for everyone representing all skin tones. While it’s great to have Black-owned brands supported by Blacks, we should set up brands to be as successful as possible.

Christian – There’s been a big emphasis has been on hiring diverse employees, but one important thing we need to do is to give credit when asking associates of color or staff of color to participate in non-billable projects like client pitches, that still contribute to bottom line.