Top NFT Intellectual Property Disputes in 2022

Alt Legal Team | December 01, 2022

NFTs made headlines throughout 2022 in mainstream press as well as in the context of IP law and NFTs. Brand owners continued to file NFT and NFT-related trademark applications with great enthusiasm. As of Oct 1, 2022, the USPTO had received over 4600 trademark applications that include or relate to NFTs.

While NFT sales have dropped throughout 2022—many outlets reporting the dramatic drop as a “collapse” or “implosion”—with the NFT marketplace proving to be so volatile and so many IP/NFT issues left mostly unresolved, this is an important area for IP lawyers to continue to watch throughout 2023.

Here’s our roundup of the most important NFT-related disputes in 2022, how they unfolded, what to watch for as they continue to evolve throughout 2023, and all of the unfinished business and unanswered questions left by settled disputes.

Alt Legal’s NFT Resources:

- What do Trademark Attorneys Need to Know About NFTs?

- Alt Legal Webinar: Fun with Non-Fungibles: NFT and blockchain basics for IP attorneys

- What IP Attorneys Need to Know About Cryptocurrency and NFTs: An Interview with Moish Peltz

Bored Ape Yacht Club and Ryder Ripps – Free Speech

This scenario involves NFTs in a rather traditional IP battle, where the IP owner uses trademark and copyright claims over a brand and artwork, while the purported infringer claims that his use is permissible under the First Amendment.

Yuga Labs is the creator of the Bored Ape Yacht Club NFTs, an NFT collection on the Ethereum blockchain. Each NFT is a profile picture of a cartoon ape that has been generated by an algorithm with unique attributes, including clothing, accessories, facial expressions, coloring, patterns, and more. The collection launched in April 2021 and has since generated over $1 billion in sales.

Ryder Ripps is a well-known LA-based artist with a large following on social media. In January 2022, he began posting claims that he believed there were connections between the Bored Ape Yacht Club imagery and language and Nazi and white supremacist messaging. Then in May 2022, he released a collection of NFTs called “Ryder Ripps Bored Ape Yacht Club (RR/BAYC).” The collection was intended to be a copycat collection of the Yuga Labs. Ripps sold 9,500 NFTs for a total of approximately $1.6 million.

Yuga Labs filed a lawsuit against Ripps claiming false advertising, trademark infringement, and cybersquatting, among other charges. Additionally, Yuga Labs vehemently denied Ripps’s accusations of racism. Yuga Labs accused Ripps of “trolling” and “scamming” Yuga Labs consumers by creating “copycat” versions of the Bored Apt Yacht Club NFTs and flooding the NFT marketplace with them.

In response to the lawsuit, Ripps claimed that his works were parodies and protests against the Bored Ape Yacht Club and that there was no consumer confusion because of a very clear disclaimer upon purchase indicating that the purchase of Ripps’s works would not provide access to the Bored Ape Yacht Club. Ripps’s lawyers also filed an anti-SLAPP motion, a motion to dismiss a suit where the plaintiff’s purpose in bringing the suit is to chill the valid exercise of free speech.

The Yuga Labs v. Ripps matter is still unfolding in court and is one to watch: even though the issues themselves are not so novel, the NFT medium may add some layers of complexity and interest. Follow the case at: Yuga Labs Inc. v. Ripps, C.D. Cal., No. 2:22-cv-04355.

Bored Ape Yacht Club and Seth Green – Stolen NFTs and NFT Licensing

Yuga Labs’ terms of service grants a license to Bored Ape NFT owners to exploit and develop the property for commercial purposes. According to the terms, “ownership” is determined by possession of the NFT, which is recorded on the Ethereum Network’s blockchain. However, the terms have created ambiguity over scenarios involving stolen and sublicensed NFTs.

Illustrating the complexities involved in the Bored Ape NFT license scheme is the story of actor Seth Green’s stolen NFT. After Green purchased Bored Ape #8398 in July 2021, he developed an animated series featuring Bored Ape #8398 and other NFTs in his collection.

However, shortly before he released the series, his Bored Ape NFT was stolen in a phishing scam and purchased in good faith by another individual. Green was left scrambling to reclaim the stolen NFT and was forced to halt the series release. Producers were unclear as to what the Yuga Labs’ terms of service were in a scenario involving a stolen NFT. Were sublicensing agreements that Green entered into involving his NFT still valid?

This puzzling scenario was never fully tested as Green was able to reclaim his NFT from the good-faith purchaser. Some have suggested that traditional laws pertaining to ownership and possession of stolen goods also apply in this scenario. For example, in New York, thieves cannot obtain ownership because good title does not pass to thieves. While blockchain will indicate who has possession of the NFT, it does not reflect who has ownership. Another applicable legal principle is that if someone unknowingly buys a stolen item, they are usually afforded legal protection. However, in the case of NFTs where all ownership is recorded on the blockchain, is it even possible for a purchaser to unknowingly purchase a stolen item?

While legal observers never got to see this case get fully played out in court, it serves as an important warning for artists looking to exploit their NFTs in 2023. With studios unwilling to take risks on releasing projects where NFT ownership and licensing terms are unclear or at risk from potential theft, artists will need to tread cautiously when entering into agreements with studios, lest their projects be cancelled due to ownership concerns. Similarly, studios will need to carefully draft agreements to consider NFT ownership and reserve the right to halt production should ownership come into question.

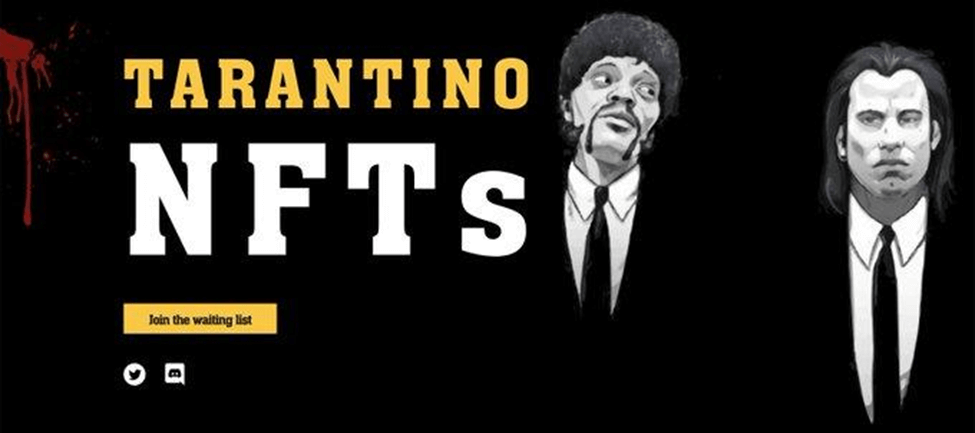

Quentin Tarantino and Miramax Pulp Fiction NFTs – Copyright and Contemplation of NFTs in Older Contracts

In late 2021, filmmaker Quentin Tarantino released a seven-item NFT collection based on the 1994 hit film Pulp Fiction. The first NFT sold at auction for $1.1 million, but the remaining auctions were cancelled as a result of the ensuing dispute with Miramax. Tarantino wrote and still owns the copyright to the Pulp Fiction screenplay, but the film studio, Miramax, claimed that Tarantino’s contract with the studio prevents him from releasing the NFTs.

According to Tarantino’s contract with Miramax, he retained rights to print publication, the making of books, comic books, and novelization (in written, audio, and electronic format), and interactive media. Tarantino’s lawyers argued that the NFTs were merely electronic copies of uncut handwritten scripts of Pulp Fiction, which would be a permissible distribution under his agreement. While Miramax retains ownership of copyright to the film, Tarantino’s NFTs exploit the screenplay, not the film. Some argue that the proper outcome is that Tarantino retains rights to exploit the screenplay with NFTs while Miramax retains rights to exploit the film with NFTs.

Ultimately, the parties decided to resolve the case with an undisclosed settlement. However, this is an important case for NFT minting and exploitation as it shows the difficulty of ascribing ownership and exploitation rights where preexisting contracts did not contemplate a world involving NFTs. In the meantime, parties must carefully contract for exploitation of NFTs and not rely on catch-all phrases or traditional copyright laws.

MetaBirkins – Trademarks and NFTs

Artist Mason Rothschild developed a collection of 100 NFTs dubbed “MetaBirkins,” displaying the famous Hermès Birkin handbag covered in various patterns, textiles, and artworks. By January 2022, Rothschild sold over $1 million in MetaBirkin NFTs. Hermès owns trademark registrations for BIRKIN and objected to Rothschild’s use of the trademark in the sale of his NFT collection. Hermès claimed that there was actual consumer confusion where consumers believed that the MetaBirkins were affiliated with Hermès. Hermès sued Rothschild for trademark infringement and dilution, misappropriation of its BIRKIN trademark, cybersquatting, false designation of origin and description, and injury to business reputation.

In turn, Rothschild asserted that he included a disclaimer stating that there is no affiliation between himself, MetaBirkins, and Hermès. Additionally, he claimed that his NFT collection is a commentary on the fur-free initiatives in fashion. As designers aim to use alternative textiles in place of fur, his NFT collection serves as inspiration for what could be accomplished with fur-free designs. Rothschild also relied on free speech claims that his art depicting the Birkin bag is protectible artistic expression under the First Amendment.

The SDNY determined that Rothschild’s MetaBirkin NFTs qualified as artistic works and were subject to the Second Circuit’s Rogers v. Grimaldi test for balancing free speech against trademark rights. The court also denied Rothschild’s motion to dismiss, finding that Hermès had alleged sufficient facts to retain all of its claims.

The case is still pending before the court as the parties fight their sides of the case. It will be important to watch as the issues unfold and the court answers questions about when NFTs rise to the level of an artistic expression protected by the First Amendment (and when they are considered commodities without First Amendment protection) and when trademark rights outweigh first amendment rights in the metaverse. Follow the case at: Hermès Int’l v. Rothschild, S.D.N.Y., No. 1:22-cv-00384.